Blog Entries

9.08.15

Vice, Magic, and the Poetics of Relation in Downtown Miami: Ruminations on the “Latinopolis”

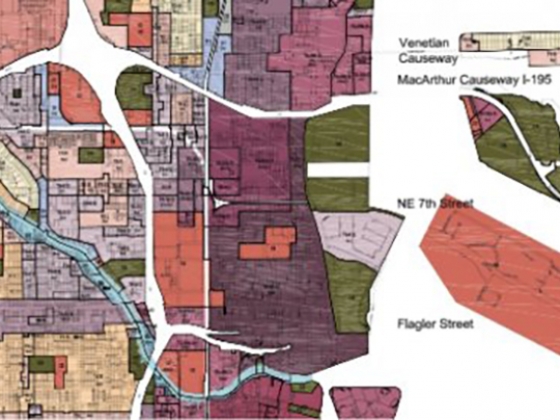

Image from map of Downtown Miami highlighting urban density, created by Duany, Plater-Zyberk & Company for the Miami21 plan. Downtown's geography is determined by natural arteries (such as the bay and the river) and by supernatural arteries, most notably the highway.

I often describe Miami’s Downtown neighborhood as ‘Detroit meets Dubai, with a Caribbean flair’ to visitors. Tall high-rises line up along the Biscayne Bay and Miami River waterfronts, an array of luxury condominiums and hotels branded as urbane and chic. These developments belie Downtown’s interior, where the legacy of mid-century modernism is apparent in the commercial and civic buildings of the district’s core. Downtown's northern section, abutting the historically black community of Overtown, remains dominated by barren parking lots. Today they are fenced in, made inaccessible to the sizeable homeless population who claim the surrounding sidewalks.

New development meets Miami’s older architectures. To the left is Centro Lofts Miami, a 37-0story condominium high rise in construction. To the right is the palazzo-style 1926 Ingraham Building, designed by iconic U.S. firm Schultze & Weaver.

Miami, popularly referred to as the “Magic City” given its rapid development, is a city of stark contradictions. While nearby neighborhoods such as Brickell and South Beach appear as cohesive apparitions of paradise, the symbolic center of Miami is vividly fragmented. New sleek developments can exist alongside grinding poverty. While club goers from all over arrive to Club Space in the wee hours for partying well beyond the sunrise, workers arrive further south, as Downtown’s center serves as a commercial core for Miami’s diverse Latin American and migrant populations.

George Yúdice, Proffesor of Latin American Studies at the University of Miami, has referred to Miami as a “Latinopolis.” He accounts for the rise of Miami as a center of Latin American trade and banking, as well as a cultural and entertainment powerhouse in Spanish language media. Miami’s rapid urban transformation in the past decade directly correlates to the city’s growing prominence as a multi-lingual center for business, trade and leisure. As the city became the Latin American elite’s favorite shopping mall and meeting point, it also became an investment. The current real estate boom is highly connected to investors from abroad, most notably Brazil, and echoes the desires of a mobile global elite to reach greater heights, physically and allegorically. Much of Downtown’s charm, however, comes from the businesses that have survived the test of time, through the first boom and bust: Richard’s Fruit and Juice Bar is a Latin American style frutería, Nuñez Fabrics still has the best assortment of lycra imaginable, and the 24-hour sidewalk corner spot Manolo & Rene Cafeteria is still whipping out coladas and Cuban sandwiches at ungodly hours.

Downtown provides a peculiar example for thinking about Miami’s ‘Latinidad.’ From the heights of new condos to the sidewalk level ventanitas selling Cuban coffee, Spanish language is a common presence. The CBD’s cleverly branded Miami Downtown Development Authority plays an active role in promoting a cohesive vision of Downtown as a prominent global city, advocating a master plan to help transform the area into the ‘epicenter for the Americas.’ This blog aims to provide personal ruminations on Miami’s transforming neighborhoods: to explore the heritage of diverse neighborhoods impacted by new classes of Latino and Latina migrants.

Perched Above the Rest

When I first returned to Miami in January 2010 I decided to give into the fantasy of condo living for one year. The excessive boom of the early-to-mid 2000s reverted into a host of foreclosures, with much of the city in economic gloom. Depreciated real estate values made rent in these luxury vaunts barely affordable. The halt of development was immediately visible from the vista of my studio apartment’s 21st floor balcony. Two identical 55-story towers adjacent to my building were largely empty from the 30th floor up. I blamed it on the building’s poor choice of lobby art (Romero Britto), but the reality remained that Miami was in a serious housing crisis.

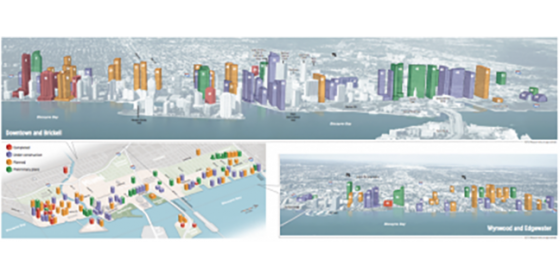

This image by the Miami Herald was a projection of Miami’s changing skyline during the heights of the first boom (2000-2007). The DDA recently released a video projection of Downtown’s continuing “Manhattanization.”

Nonetheless, the boom left an indelible mark on the city. Downtown experienced what was termed as “Manhattanization.” Plans for opening a state of the art Museum Park remained, as new bars and restaurants began to cater to condo residents and international tourists. During the years of the bust, Downtown became, for a lack of better words, hip.

Today, the dramatic transformations of the 2000-2007 boom seem to repeat, perhaps at a more grandiose scale. A host of new real estate and commercial ventures are moving the development further west from the bay. No project is more prominent than the proposed Miami Worldcenter, an ostentatious and ambitious megaproject incorporating a large luxury mall, condominiums and hotels. The developers promise to build a world-class city within a city, an urban destination connected to multiple modes of transport. Thus far they have purchased over 25 acres of land, and sold properties to a wide array of the international elite, seasonal residents looking for a fabulous escape in its gleaming glass towers.

Banner for Miami Worldcenter, fluttering in the wind along NE 2nd Avenue near 8th Street.

The new urban enclave will wrap around the Network Access Point (NAP) of the Americas, a large building topped by three mysterious white geodesic globes. An important data center for telecommunications in Latin America, NAP of the Americas will serve as anchor to Miami Worldcenter’s global ambitions. NAP of the America’s dominant presence within Downtown’s barren northern extremities will be dwarfed, however, by the new development. One 60-story tower, the Paramount Miami Worldcenter, promises to offer the most enviable recreational area on its 9th floor amenity deck, including a full soccer field. Together the project represents an urban dreamscape, a fantasy of a better connected world for the mobile elite.

As for now, the area remains one of empty lots and desperation. Promotional banners for the megaproject line the fenced in lots, featuring expansive views of the project as well as images of attractive models enjoying urban living. With construction slated to begin very soon, it is unclear whether the urban dream of Miami Worldcenter will succeed. Previously large urban malls, such as the nearby Omni International Mall of Miami of the 1970s, ultimately flopped. And with the nearby Brickell City Centre in construction and proposals for the world’s biggest mall elsewhere in the county, there may be plenty of competition.

Los Arcados de Miami

Prior to the condo boom of 2000-2007, large parts of Downtown remained vacated. A sea of parking lots surrounded its civic core, a legacy of mass suburbanization in the mid-to-late 20th century. Downtown was deemed a neighborhood unfit for recreation, a no-go zone within a city still recuperating from the drug wars and racial riots of previous decades. Still, Downtown had a notably Latin American flair within its main core, as seen in the urban malls extending east from the Miami-Dade County Courthouse, a 1920s 28-story neoclassical tower that became Miami’s first major skyscraper.

Downtown’s civic and commercial core. To the left is a long standing mural on SE 1st Street and 1st Avenue, alongside the Metromover. To the right is a view of Miami’s older skyline, including the 1928 Miami-Dade Courthouse at the far right of the photograph.

Along Flagler, SE 1st and NE 1st Streets are various galleries – interior malls bifurcating Downtown’s urban fabric. Mostly built between the 1960s and 1980s, they appear as modernist vestibules of shopping. They are, in actuality, an urban solution for the pedestrian frequented area of Downtown, providing ventilation and relief from the subtropical heat. Cross block arcades became a common feature throughout downtown as early as 1926, with the Shoreland Arcade on NE 1st Street. The arcade was the base for a never-built 20-story office tower, and only part of it remains today. It's alluring Art Deco façade stands as a reminder of the boom and bust model that has long dominated Miami’s development.

Upon returning to Miami in 2010, I associated these arcades with the shopping areas one would typically see in places like Centro in Santiago de Chile and Mexico City. The arcades often contain cheap electronics and jewelry stores, greasy food spots, and a variety specialty stores. The presence of diverse Latin American businesses provides a particularly global vibe. Unlike the glamorous shopping experiences promoted by enterprises such as Miami Worldcenter and Brickell City Centre, the arcades of Downtown Miami comprise of modest ma-and-pa shops, geared to a lower income patron.

One such example is the Ultramont Mall, an arcade connecting SE 1st Street to SE 2nd Street along 1st Avenue. The building is lined with shops along the streets as well as within its expansive vestibule. It is painted an ugly mustardy yellow and hues of blue, as seen in its blue columnar pilasters running along the street-side exterior, and features dark windows and untimely white tiles. Most striking is the building’s postmodern employment of geometric forms, dating the architecture to the 1970s-1980s era. Spherical, globe-shaped lights line the interior as the pitch-roof glass ceilings meet at a cross axis in the center. A rainbow-colored fluorescent sign welcomes visitors into its vast, often unoccupied space.

When I first visited Ultramount Mall in 2010, I left with a sense of awe. Its off-putting use of color and geometric shapes recall the Saved-by-the-Bell style pastel pastiche of the nearby Bayside Marketplace, Downtown Miami’s most generically touristy mall. At the same time the space was rather unnerving – while comprised of a random yet exciting array of businesses, including a dollar store, a run down hair salon, a photography school, a hippie incense and oil gift shop, and a Brazilian restaurant, the arcade felt incredibly abandoned. The lack of a human presence caused my imaginations to run while – within its crisscrossing vestibules I imagined an ideal setting for a Miami Vice-themed zombie movie, set to a 1980s Freestyle music soundtrack.

Other arcades in the Downtown area recall the dated and unnerving aesthetic of Ultramont Mall. The Galleria International Mall on NE 1st Street and 3rd Avenue, anchored by a Marshalls retail store on Flagler Street, recalls the drab, uninviting ambience of Ultramont. Bright fluorescent lights are accompanied by neon signs in the main passageways. Unlike the luxury spaces of Miami’s waterfront, the retail arcades of Downtown Miami’s interior do not seduce the consumer. Rather, they present the economic necessities and desires of Miami’s migrant and labor classes, who frequent these malls and support their varied businesses.

While unpleasant, these ugly modernist mazes of austere consumerism do intrigue. On a recent trip to the Galleria International Mall, I ventured down a strange corridor that forked from the main passageway connecting NE 1st Street with Flagler Street. Nestled in one corner was a seemingly abandoned Brazilian steakhouse next to a small multi-purpose Filipino convenience store, which is converted into a steamy buffet spot every weekend.

I noticed, upon seeing the Filipino workers enjoying their lunch, that these spaces provide a semblance of home for Miami’s migrant and itinerant populations. Perhaps this is why Los Arcados de Miami felt so Latin American to me. While Latin American wealth fuels Downtown’s hyperdevelopment and growing stature as a global city, it is the nondescript businesses lining the passageways and streets of Downtown that give the area its notably Latino and international grit. These diverse enterprises show that globalization is not merely a mirage for Miami’s neoliberal fantasies.

Next to the Filipino shop I discovered an Indian market, a rarity in Miami-Dade County. Excited by the prospect of buying curry leaves and masala chai spices, I chatted with the owners of Indian Prem grocery store about my love of chutney, travels through India, and Miami traffic. I was told that their clientele are largely cruise ship workers, contracted to work on the ships eight to nine months out of every year, often in very questionable conditions. With Downtown adjacent to the Port of Miami – the cruise ship capital of the world – shops like Indian Prem and the Filipino market and buffet present micro-economies within the bustle of Downtown. A question remains on whether new transformations will permit these types of businesses to thrive, as Downtown is reimagined as the retail Mecca of the Americas par excellence, in a city that appears to be Latin America’s premiere luxury shopping mall.

Poetics of Relation – From the Museum to the Streets

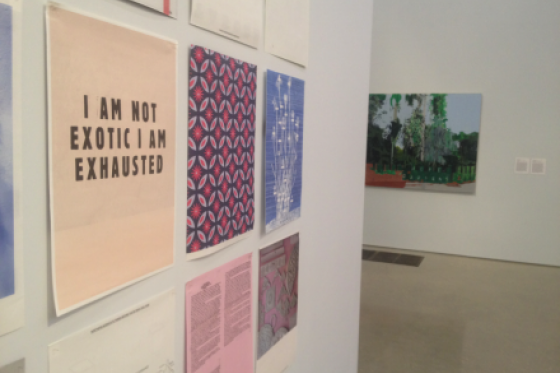

Currently, the Pérez Art Museum of Miami (PAMM) is hosting an exhibition that explores local, regional, and global cultural currents through the philosophy of Edouard Glissant. Titled “Poetics of Relation,” and curated by Tobias Ostrander and Tumelo Mosaka, the exhibition features the work of six contemporary artists, many from diasporic and exiled communities around the world. Drawing inspiration from the famed Martican poet and intellectual Èdouard Glissant’s book Poetics of Relation, the exhibition featured artworks that drew from themes of exile, landscape and place. Visually and thematically, the exhibition directly concerned the place of Miami, as a nexus of the Caribbean and the world.

Works by Tony Cappellán and Xaviera Simmons.

In Poetics of Relation, Glissant explores identity through the framework of errantry. Glissant makes sense of the Caribbean through a notion of errantry, where the region’s colonial vestiges and tropical landscapes contribute to our understanding of are place in this world. For Glissant, the Caribbean is an archipelago where the terms of Relation appear most vividly – it is a sea that diffracts. At the edge of the Caribbean, Miami has become a major economic and cultural nexus for the region. In many ways, it is the region’s anchor to the mainland. Hence, it is of little surprise that the ocean figures predominantly in the exhibition, as seen by the works of Tony Cappellán and Xaviera Simmons.

As a city of exile and errantry, the ocean has determined the route of many Miami residents’ arrival. It is also visibly present from the museum. No stranger to controversy, the Herzog & de Meuron-designed museum is itself an imposition onto the terrain of Downtown – one of its luxury amenities. Formerly named the Miami Art Museum, it was founded in the core of Downtown as a local, public initiative. There was uproar when the museum took the moniker of Miami’s biggest real estate kingpin, who claimed the controversy was akin to racism. Whether a wealthy Cuban developer from Argentina understands the terms of racism in the context of Miami remains questionable. However, the museum has moved well beyond the original controversy of propriety, expanding its staff and creating an incisive programming that reflects Miami’s place as an “Epicenter for the Americas.”

Works by Yto Barrada and Hurvin Anderson.

“The Poetics of Relation” exhibition is accompanied by thematic displays of the museum’s permanent collection, entitled “Global Positioning Systems.” A stroll through the museum provokes and engages. While the museum, as an institution and as a structure, is in bed with Miami’s hyperdevelopment, PAMM also provides a refreshing space for thinking about the city’s relationship to its broader regional and global settings. Art and scholarship become a means to interrogate the mythology of Miami’s ascendency as well as the social, political and environment perils facing the region.

Image from http://lizmirabal.tumblr.com/.

The astute artistic reflections within “Poetics of Relation” followed me as I left the museum. Taking the Metromover - the area’s free mass transit automated people mover – I immediately noticed a series of poems on the surface of warehouse-like buildings. One proclaimed “Sticks Stones Broken Bones / Walls Malls Basketballs.” Located within Downtown’s northern hinterlands, they stood out from their setting, amid vacant parking lots. One poem artfully recalls the seduction of orange blossoms, seemingly an ode to Miami’s founder Julia Tuttle. Each of the poems are ironic, engaging and clever, relative to the spectacle that is the city’s ascendancy.

Upon research, I discovered that these tongue-in-cheek poetic fragments were actually commissioned by the Miami Worldcenter, the architectural behemoth that will help ensure the ephemerality of these murals. The poetics of Miami seem inherently contradictory. Or at very least, urban art has become totally institutionalized, a means for developers to enhance an image of a neighborhood still in transition. With walls, malls, and basketballs, no less.

Fredo Rivera earned a doctorate from the Department of Art, Art History, & Visual Studies at Duke University. He is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Florida Atlantic University's School of Architecture.